The Frescoes

|

My

father considered himself first and foremost a muralist. He studied

the techniques of painting al fresco in Florence, Italy, from 1924 to

1926. Upon completing his studies he received commissions to paint the

frescoes for the Spanish consulate in Hendaye, France, the Administration

Building for the University City in Madrid, the entry hall to Madrid's

Museum of Modern Art, the meeting hall of Madrid's Casa del Pueblo,

and the Monument for Pablo Iglesias. Of all these large ensembles, only

the relatively small fresco he painted for the Museum of Modern Art

still survives. Everything else he painted before the war was destroyed

by the war or, under Francisco Franco's orders, by the fascists after

the war. |

Madrid Museum of Modern Art

|

This fresco was painted for the entryway of Madrid's Museum of Modern Art in 1934. It somehow survived the fascists' fury. In the 1970's, after Franco died and democracy had returned to Spain, it was restored by the Ministry of Culture. Here is a photograph of it before the restoration. It is currently in storage in the Reina Sofia Museum in Madrid.

Women Mural al fresco: 180 x 220 cm. |

3 - Continue Aesthetic Survey or Return to Menu

* * *

Love Peace Hate War

|

My father received a commission to paint the murals for the Spanish Pavilion of the 1939 Worlds Fair in New York. And when he arrived in New York that January, beginning an exile which would last 37 years, he painted five large panels al fresco. These have variously been called a "Poem of War" and "Love Peace Hate War;" the latter becoming the final title. The panels portray five aspects of the war: "Flight," "Pain," "Hunger," "Soldiers," and "Destruction." They were finished but they were never hung in the Spanish Pavilion. They were never hung for obvious reasons. In November they were shown instead at the Associated American Artists' Gallery at 711 Fifth Avenue. Ernest Hemingway and Juan Negrin, Premier of the Spanish Republic, acted as hosts at the preview which was held on the evening of the sixth. And Negrin read a poem Archibald MacLeish wrote characterizing each of the five panels. MacLeish himself didn't appear at the preview, perhaps because of the "feud" he was having then with Hemingway over the funding of The Spanish Earth, a film promoting the Loyalist cause. And family lore has it that MacLeish took back his poem as a result of some political heat he received for writing it. MacLeish's views on the war, though, were well known and he wrote several poems promoting the Loyalists but, whatever the cause, the poem has completely disappeared, was never published, and nobody seems to know what became of it. As for those five panels which created such a stir so many years ago, they too eventually disappeared, emerging once again in the early 1990's within the isolated hallway of a Greenwich Village pornographic movie house. In the early forties my father claimed that a roof had flooded and collapsed destroying all the frescoes. What actually occurred was that he had secretly hidden them in the dark hallway of the Bleeker Street Cinema, whose owner was sympathetic to the Republican cause. (This was long before the theater became a porno movie house.) And hiding them in this manner, my father had been able to prevent the Franco government from reclaiming and destroying his frescoes. At this time they remain in storage: damaged, forgotten and neglected. In the early nineties an attempt was made to retrieve them, but the amount of money offered didn't satisfy the owner of the pornographic movie house. If they had been retrieved they would have been restored and would be hanging in the same gallery, in Madrid's Reina Sofia Museum, in which Picasso's Guernica hangs.

Update: on February 2, 2007 the University of Cantabria, in Santander, Spain, bought these frescoes. They have been restored and hang now at the university. The opening occurred on October 10, 2007. Before and After the Restoration Cover and Text of the Opening's Catalog Los Otros Guernicas (A documentary on the Love Peace Hate War murals.) |

|

| Soldiers |

|

| Destruction |

|

| Hunger |

|

| Pain |

|

| Flight |

Studies for the Love Peace Hate War murals

The Don Quixote Murals

| He was to paint one more major ensemble of frescoes. From September 1940 until June of '41 he was the "artist in residence" of the University of Kansas City, in Kansas City, Missouri. Here he painted six large panels, covering 375 square feet of wall space, in the Language Arts Building, which depict Don Quixote in the modern world. These are located in Haag Hall at what is currently the University of Missouri in Kansas City, Missouri. |

|

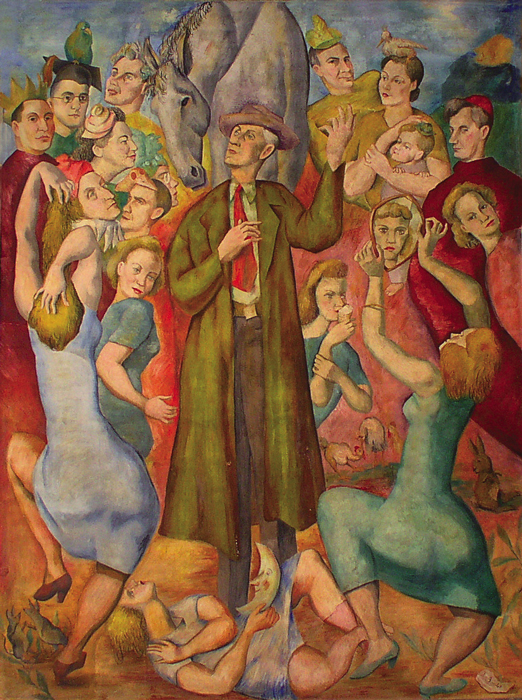

| The Ideal World of Don Quixote In the ideal world of Don Quixote the Don is portrayed standing in the center of the mural surrounded by those human types he most admires, abstracted and dreamily distant in his pose and appearance. Poets, philosophers, statesmen, beautiful women, artists, happy children, ideal humanity surrounds him as he dreams oblivious to the whirling of society "in its own fantastic carnival dance," as my father explained it. My mother appears in this mural in the upper right with a little bird resting on top of her head and I appear in her arms with a tiny hat on mine. My father completes the family portrait. |

|

Sancho Panza Sancho appears as a burly working man with a cigar held high up in his hand as he sits on his donkey, Dapple, with two obese peasant women looking on from a distance and the ground beneath Dapple's feet is covered with a harvest of good food. |

|

Don Quixote In one panel Don Quixote, his face unlined, honest, and sensitive, appears seated up on his steed, Rocinante, with his arms helplessly criss-crossed holding out a lance and a rose. "This is the idea," my father explained through his interpreter at the opening. In this panel the Don is represented "as he appears to the average person: a queer, gangling figure seated on an ancient mode of transportation with the cape of romanticism falling from his shoulders. Assuming a strained and exaggerated gesture, he offers impotent protection with one hand, and with the other momentary beauty (a flower) to two quite understandably startled workers from the spade-is-a-spade world." |

|

| The Ideal World of Sancho Panza This is the spirit of Sancho Panza: "whose dreams never stray very far from his nicely rounded stomach." In his ideal world he is shown as he appears at a country dance. "When Sancho approaches the social whirl, he does not stand apart; he does what seems to him most natural. He steps in and whirls with every pretty girl passing by... Sancho is that healthy average man who enters wholeheartedly into the gaiety of living whenever, wherever, however he finds it." |

|

|

The Bitter Moral After seeing Sancho and the Don in their ideal worlds we see them in the world of modern reality. Against his wishes Sancho becomes the governor of an island. And in what may be the best conceived panel of the six he is portrayed as he governs. Here we see common grotesques, faces known to all of us, humanity at its worst as we see it daily on the streets, on the job, in the news everyday and on TV. "He [Sancho] proves himself just, the friend of the weak and oppressed. He unmasks fraud, interprets the laws wisely, although he can't read them. Guileless of pride and greed, he governs with such peasant honesty that his people fail to understand him, cause uprisings, turmoil, criticism. They laugh behind his back and carry him in effigy. When he resigns, they come to appreciate him, but at this moment the bitter moral seems to be that nothing prospers save folly." |

|

|

Don Quixote in the Real World But for Don Quixote the greatest horrors are reserved. The world at the moment the murals were painted was plunging into world war. Fascism was international in nature and was not confined merely to Europe. The classic device of portraying a monster opening its maw wide and revealing the horrors within was employed. The Don is shown here standing by his horse, his pipe contemplatively held up toward his face, impotently surrounded by human horrors of all kinds. His face is honest, clear, and simple: unrecognizable to passersby on the street and unpretentious. And the vision we are offered is not the man on the street's but of the eternal outsider looking on. |

Studies for the Don Quixote murals

Photos of the Artist painting the Murals